Cello Suite No.1 in G major, BWV 1007 (Bach, Johann Sebastian). Ms Harvey isolates the many problems the first Bach Cello Suite offers, measure by measure, movement by movement. She has created effective etudes to treat these problems. She then helps the student put these elements back together. Introduction “Monophonic music wherein a man has created a dance of God.” That is how Wilfrid Mellers, in his book, Bach and the Dance of God, describes the Six Suites for Unaccompanied Violoncello by J.S. Bach.1 This pithy yet provocative preamble comprises several of the important threads one may consider when studying and performing this repertoire.

The Cello Suites of Johann Sebastian Bach

Bach Cello Suite 1 Sheet Music

Cello Suite No.1 in G major, BWV 1007 (Bach, Johann Sebastian).

To see a World in a Grain of Sand

And a Heaven in a Wild Flower

Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand

And Eternity in an hour

- William Blake, Auguries of Innocence

Overview

Bach's six suites for unaccompanied cello occupy a special place in the repertoire for both player and listener. Cellists regard the suites as sacred touchstones for their instrumental art demanding the utmost in technique, interpretation and expression requiring years if not a lifetime to master. Listeners treasure a unique sound palette featuring the warm, deep and wooden sonority of the intimate solo cello so close to the natural human voice presenting a collection of musical short stories rich with elegant designs, wide-ranging emotions and transcendent reflections. A complete performance of the six suites permits a total immersion: to acclimate, yield and expand into the astonishing diversity of what might at first seem constrained by its minimal means, its stark simplicity. Like so many comprehensive sets of music by Bach, the suites appear to encompass a whole universe possibilities, a world in a grain of sand, eternity in an hour.

Bach composed the cello suites sometime around 1720, the same time (and most likely before) he wrote the equally astonishing six partitas and sonatas for solo violin. During these years from 1717-1723, Bach was employed as the Kapellmeister to Prince Leopold in the court of Anhalt-Köthen (Cöthen). Prince Leopold was a music lover who also retained a talented group of orchestral and chamber musicians suitable for Bach's finest inspirations. Unusually free from the demands for religious music typical of his other employers, under Prince Leopold, Bach composed some of his finest secular instrumental music during these years including the Brandenburg Concertos, the first book of the Well-Tempered Clavier, and, of course, the cello and violin suites. We cannot precisely date the suites because a manuscript in Bach's own hand has never surfaced. There exists a manuscript by his second wife, Anna Magdalena, as well as a possibly earlier manuscript by the organist and friend Keller (c.1726). It seems the suites were not officially published until 1824 (in Paris), at least one hundred years after Bach composed them, and even then, they were largely regarded as exercises or studies for private consumption, certainly not for public performance. Indeed, at this time in history, Bach himself would have been considered an antiquated obscurity known only to certain professional musicians such as Felix Mendelssohn who would daringly mount a 'debut' performance of the St. Matthew Passion a few years later.

The suites languished in near obscurity until a 13-year-old Catalan cello student named Pablo Casals discovered a printed copy at a second-hand bookseller in Barcelona in 1890. Casals began a lifelong obsession with the suites practicing them for well over a decade before presenting them in public performance. It would take Casals nearly half a century following his discovery to record the suites: made between 1936-1939, the Casals recordings finally introduced the cello suites to the larger world establishing them firmly in the repertoire of masterworks. Today, there are hundreds of printed editions and several dozens of recordings by the world's greatest cellists. Indeed, like much of Bach's extraordinary 'absolute' music that seemingly transcends any particular instrumentation, the suites have been transcribed and recorded for a wide range of instruments and ensembles.

The Baroque Dance Suite

The suite was a dominant form of instrumental chamber music in the late Renaissance and Baroque eras. A suite comprises a set of idealized dances (e.g. for listening, not dancing), which, by Bach's time, represents a broadly European amalgam including dance types from Italy, France, Germany, England and Spain. Each dance features a particular tempo, rhythm and character contributing a pleasing diversity of mood and expression to the composite suite. All six suites include four standard dances at their core:

Allemande – From the French word for 'German', moderately paced in duple rhythm (2 or 4 beats to a measure), by convention, often placed first. These are often the most complex movements of Bach's suites.

Courante – A triple meter dance with regional differences here historically following the swiftly running Italian Corrente.

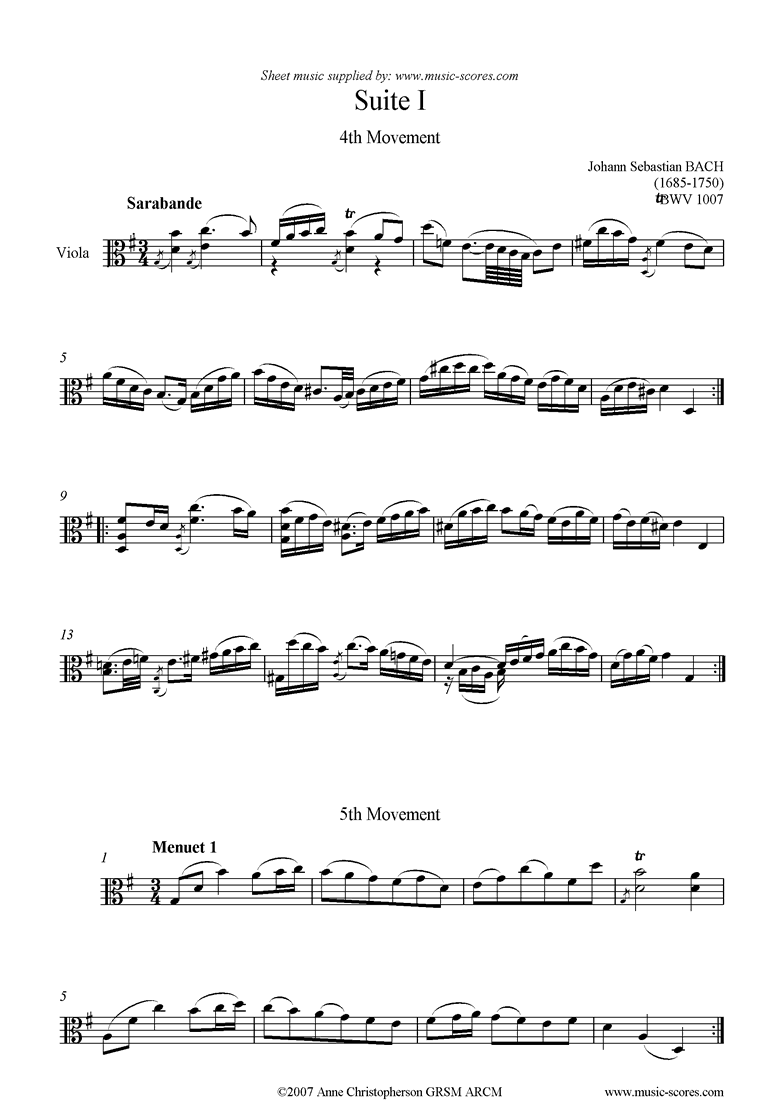

Sarabande – Originally a sensuous dance of African and South American origin that made its way back to Spain. In France and Germany, the Sarabande assumed a slow, stately quality using a triple meter with an emphasis on the second beat. In Bach's cello suites, the Sarabande tends to be the deeply expressive emotional heart of the music.

Gigue – The French spelling of the lively dance from England otherwise known as the Jig. With a rocking compound triple meter (e.g. featuring beats in two's and three's) and a jolly demeanor, the Gigue is typically the energetic finale of a suite.

Like many suites and sonatas of the era, Bach begins each suite with a Prelude, an introductory movement historically used to ensure the tuning of the instrument, warm up the fingers, establish the primary tonality of the piece and possibly display some spontaneous virtuosity. It has been said by many that the essential character of each suite is fully revealed in the opening of the prelude often with thematic linkages across the other dance movements.

Finally, in the penultimate movement of each suite before the Gigue, Bach interpolates a pair of additional dance movements in a lighter 'galant' style often called the Galanterien (German) to distinguish them from the essential four main and more substantial dances of the suite. Whether Minuet, Bourrée, or Gavotte, each originally fashionable dances from the French court with their own distinctive meter, accent and character, Bach supplies two of each with the first reprised in the manner that persisted in the minuet and trio of the Classical era, e.g. Minuet I – Minuet II – Minuet I.

Suites V and VI: Special Considerations

Bach Cello Suite 1 Mp3

While it seems indisputable that Bach's suites were indeed composed for the cello, the last two suites raise special considerations. The fifth suite calls for a special tuning of the cello – technically called scordatura – where the 4th and highest string is tuned down in order to facilitate chords and provide an especially rich sonority. It is up to the cellist whether to use this non-standard tuning or to play the suite with technical adjustments to accommodate the standard. The sixth suite was actually composed for a cello with 5 strings (one more than usual), a special instrument of Bach's time and even possibly his own invention that has never quite been identified. The last suite hence spans a wider sonic range, that, again, the cellist is likely to accommodate on a standard 4-string cello.

Bach Cello Suite 1 Youtube

Suites for Solo, Unaccompanied Cello (senza basso)

Bach Cello Suite 1 Guitar

Most chamber music of the Baroque era, even when titled 'solo' called for a main instrumentalist plus a group of one or more additional players known as the 'continuo', 'basso continuo' or just 'basso.' While the main instrument took the melodic lead, the continuo group supplied a crucial bass line plus the harmony, typically with an instrument capable of playing chords such as the harpsichord or the lute. Naturally, Bach's cello suites are written for a true soloist, without basso continuo. The instruments of the violin family including the cello are supremely capable of playing single note melody lines but have a much more difficult time playing chords, multiple notes (e.g. multiple strings) simultaneously, the essence of harmony. There are numerous places in the suites where the cellist is called upon to play 2, 3 and even 4 note chords (or 'stops'), yet the majority of the music features single-note lines without chords, seemingly without harmony. Yet one of the great miracles of Bach's music for solo instrument (even in pieces for keyboard) is the rich harmony and harmonic motion accomplished by implication: harmonies are formed by a succession of arpeggiated notes – one at time – and our listening mind connects them into chords after the fact. In many ways, the implied harmonic motion of the suites is their most affective quality.

The miracle of these suites for solo cellist goes further. Bach is remembered as a supreme master of counterpoint and polyphony: music formed by more than one voice or part playing simultaneously. As with the magic of harmony implied overtime in a kind of time-lapse development, Bach similarly implies a polyphonic texture as if the single cellist were really multiple cellists, each playing within a certain range with call, response and imitation weaving the several parts into a multiplicity of voices. This astonishing effect is the product of the composer, the capable cellist and the keenly attentive listener all of whom participate in constructing the illusion.

The Composite Set of Six Suites: Coherence on a Higher Order

Bach was a master of composing sets and collections that encompass profound variety and diversity within a single rubric. There is the rich variety of movements within each suite, but, naturally, variety on a higher level as we move across all six suites. Each suite is composed in a different key signature with two of the six in a minor key. Some of the suites are bright and exuberant; others are dark, melancholy and deeply reflective. Indeed, the mood will change within each suite itself, even within each movement, on a turn of phrase, even a fleeting gesture. The progression of suites from one to six seems to demonstrate a progression of complexity, intensity and length with the 5th suite being the most 'emotionally profound', the 6th suite being the longest and perhaps most complex, certainly, as a fitting finale, the most triumphant. While it may challenge the stamina of the listener and surely the performer, a complete performance of all six suites is an epic journey of a singular kind reserved for the rare occasion when time and place converge into a supreme experience of the very highest order: A spiritual ritual.

-- Kai Christiansen, founder of the chamber music exploratorium at earsense.org

© Kai Christiansen Used by permission. All rights reserved.